Staying fit and healthy is a top priority for many people, but health can be defined in many ways and is not necessarily simply being free of illness or injury, or having a “normal” weight. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” Clearly, there are many aspects contributing to our overall health.

One of these aspects is our metabolic health. Metabolism refers to all the chemical processes that are continuously happening within our bodies in order to sustain us, which fall into two broad categories:

- Catabolism – the process of converting food into energy by breaking down complex structures into smaller components, thus releasing energy

- Anabolism – the process of capturing that energy and using those smaller components to build up and regenerate our own human structures

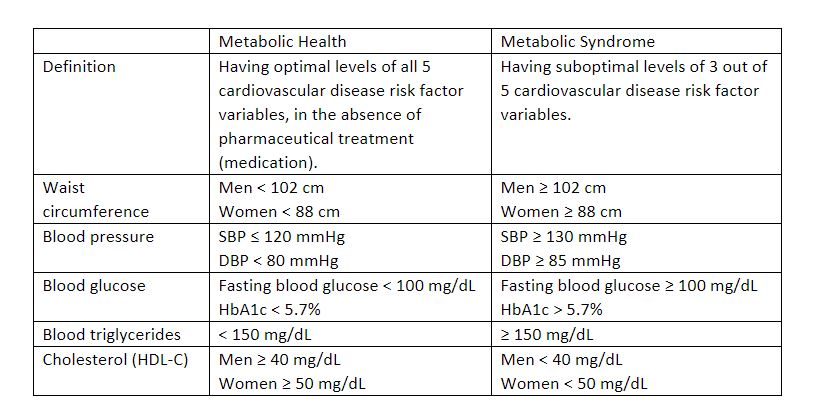

When people think of metabolism and metabolic health, weight is often the first thing to come to mind. However metabolic health is more complex than just weight and encompasses the risk of heart disease, diabetes and stroke. Whilst there is no standard definition for “metabolic health”, researchers from the University of North Carolina, USA1, used optimal levels of the five biological variables traditionally associated with cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome risk to define metabolic health and determine its prevalence.

These variables are:

- Waist circumference

- Blood pressure

- Blood glucose (including HbA1c)

- Blood triglycerides

- Cholesterol (high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-C)

The researchers determined that metabolically healthy people have optimal levels of all five of these variables. Interestingly, and concerningly, the researchers found that < 20% of American adults were metabolically healthy. This decreased to just 12.2% when the most restrictive cutoff points were used. The researchers noted that an elevated waist circumference alone is only weakly associated with cardiovascular disease risk, but even when this variable was excluded, only one-third of ideal weight (as defined by BMI) adults were considered metabolically healthy. This highlights the need to look beyond the scales when determining metabolic health.

Related to “metabolic health” is “metabolic syndrome”. Metabolic syndrome is diagnosed when a person presents with suboptimal levels of 3 out of the 5 biological variables associated with cardiovascular disease risk. It is estimated that around 22–34% of the adult population2,3 has metabolic syndrome and is therefore at risk of developing cardiovascular disease, diabetes or having a stroke.

The risk factors for developing metabolic syndrome include central obesity (i.e. excess fat around the middle), insulin resistance, age, inactivity/sedentary lifestyle and genetics.

Figure 1: Complications/health outcomes that can arise as a result of having metabolic syndrome/poor metabolic health

Closely related to metabolic syndrome and with overlapping aspects is prediabetes. People with prediabetes have elevated blood sugar (glucose) levels, but not high enough to be classed as diabetes (prediabetes: fasting blood glucose of 100 – 125 mg/dL; diabetes: fasting blood glucose of > 125 mg/dL). Prediabetics are often also overweight with central belly fat and have high blood pressure.

Prediabetes and metabolic syndrome have also been referred to as inflammatory syndromes and are characterised by hormone imbalance on a biochemical level. Catabolic hormones include adrenaline, cortisol, glucagon, and cytokines, which are predominantly associated with stress and inflammation. Anabolic hormones include insulin, growth hormone, testosterone, and estrogen, which are primarily reproductive. Insulin and glucagon work in concert to maintain blood glucose levels by coordinating the absorption of glucose into tissue such as muscles. Crucially, all of these hormones work together and influence each other in feedback loops to maintain homeostasis. An imbalance in any of these hormones has follow-on effects throughout the system, contributing to excessive weight gain or loss. Through feedback loops, even catabolic reactions using energy such as chronic inflammation lead to increased anabolism and subsequent weight gain. While this complexity can make metabolic syndrome and prediabetes difficult to resolve, it also means that there are multiple entry points through which to address underlying problems and improve metabolic health.

To improve your metabolic health and reduce the risk of developing metabolic syndrome and associated diseases, you should:

- Eat a healthy diet. Consume a range of high-fibre foods, fruits and vegetables, lean meats and plant proteins, and reduce/avoid your intake of processed foods, sugary foods (particularly those with added sugar) and foods with high levels of saturated fats, trans fats, cholesterol and salt.

- Obtain/maintain a healthy weight. If you are overweight or obese, a loss of around 5-10% can halve your risk of developing metabolic syndrome/diabetes by helping to reduce blood pressure, blood sugar and cholesterol.

- Partake in regular physical activity. This will help to improve blood pressure and cholesterol. Moderately strenuous exercise that makes you breathe harder is best. Aim for around 30 minutes a day / 150 minutes a week.

- Don’t smoke. Smoking can increase blood pressure and insulin resistance. It can also cause inflammation in the body.

- Reduce/manage stress. Chronic stress has been linked to an increased risk of metabolic disease, including obesity, cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

- Get regular check-ups. Early diagnosis of any issues means you can get onto making any required changes sooner and reduce long-term health complications.

References:

- Araujo, J., Cai J., Stevens J. Prevalence of optimal metabolic health in American adults: national health and nutrition examination survey 2009 – 2016. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders, 2019, 17(1): 46-52

- American Hearth Association https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/metabolic-syndrome/about-metabolic-syndrome, accessed 14 April 2021

- Moore, JX., Chaudhary N, Akinyemiju, T. Metabolic Syndrome Prevalence by Race/Ethnicity and Sex in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–2012. Preventing Chronic Disease, 2017, 14: 160287